In London, the pulse of the city doesn’t slow down after sunset-it transforms. From the smoky basements of 1920s jazz cellars to the neon-lit warehouses of East London, London’s dance clubs have always been more than just places to dance. They’ve been laboratories of culture, rebellion, and identity. Every era brought new sounds, new styles, and new crowds, but one thing stayed constant: London’s clubs didn’t just reflect the times-they shaped them.

1920s to 1940s: Jazz, Prohibition, and the Birth of Underground Scenes

When Prohibition swept across the Atlantic, London didn’t ban alcohol-but it did push drinking and dancing underground. In Soho, tucked behind unmarked doors on Wardour Street, speakeasy-style clubs like The Cave and The Nest became havens for jazz musicians, artists, and working-class Londoners. These weren’t fancy venues. They were damp, dim, and loud, with pianos played by Black American expats like Duke Ellington and Sidney Bechet, who found more freedom in London than at home.

Women danced the Charleston in bobbed hair and fringed dresses, defying Victorian norms. The music was raw, the crowds mixed-Black, white, working class, and bohemian. Police raids were common, but the clubs always reopened. This was the first true London club culture: illegal, electric, and deeply human.

1960s to 1970s: Mod, Psychedelia, and the Rise of the Discothèque

By the 1960s, London was the epicenter of youth rebellion. Clubs like The Flamingo in Wardour Street became temples of Mod culture. Young men in tailored suits and parkas danced to Motown and Northern Soul, while girls in mini-dresses and go-go boots moved to The Who and The Kinks. The Flamingo’s owner, Giorgio Gomelsky, didn’t just book bands-he created scenes. He’d play records after live sets, letting the crowd dance to soul 45s until dawn.

Then came the psychedelic era. In Chelsea, The Scotch of St. James hosted late-night parties where The Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix, and Eric Clapton mingled with artists and aristocrats. The music got louder, the lights got weirder, and the drugs got more experimental. This wasn’t just nightlife-it was a social revolution.

By the late 70s, disco arrived. In the West End, Studio 54 London (a short-lived but iconic clone of the New York original) opened in 1978. It didn’t last, but it proved London could match global trends. Meanwhile, in the East End, pirate radio stations like Kiss FM were already laying the groundwork for what was next.

1980s to 1990s: Acid House, Rave Culture, and the Illegal Warehouse Explosion

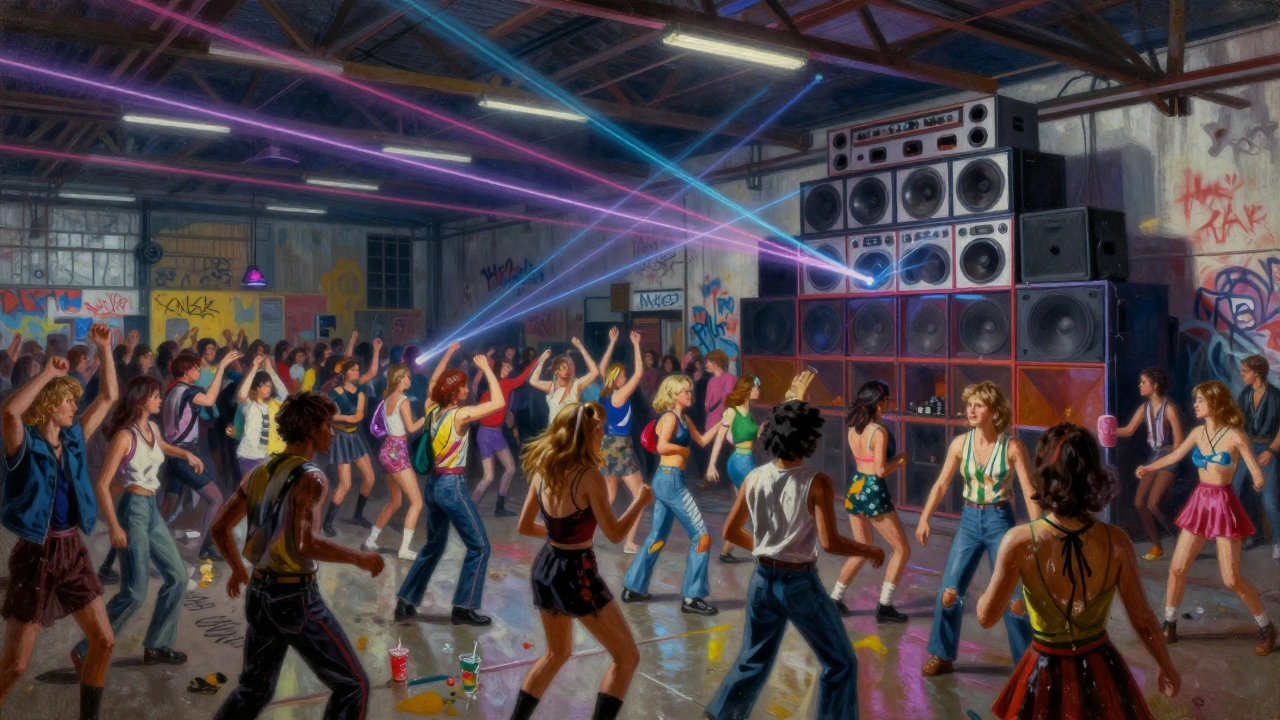

The 1988 summer of love changed everything. Acid house, with its hypnotic 303 basslines and rave flyers hand-drawn in Brixton, spread like wildfire. Clubs like The Hacienda in Manchester drew national attention, but London’s underground was bigger, wilder, and more decentralized.

Empty warehouses in Peckham, Walthamstow, and Hackney became epicenters. One famous spot, The Black Box in a disused freezer unit near Canada Water, hosted 2,000 people on a Friday night with no license, no security, and a sound system built from car stereos. The police would raid, but by the time they arrived, the crowd had vanished into the night, leaving behind only broken glass and sticky floors.

These weren’t just parties-they were acts of resistance. Thatcher’s government had cut funding for youth centers, so young people built their own. The legal system responded with the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994, which targeted raves. But the scene didn’t die. It adapted. Smaller clubs emerged. Sound systems moved indoors. And by 1996, the first legal superclubs like Ministry of Sound opened in Elephant & Castle, turning underground energy into a global brand.

2000s to 2010s: The Corporate Club Era and the Fight for Survival

Ministry of Sound became a global franchise. Soho’s clubs got gentrified. Fabric, opened in 1999 in Farringdon, became the gold standard for serious techno heads. Its sound system, designed by Martin “Marty” Smith, was so powerful it could be felt in the street outside. It wasn’t just a club-it was a pilgrimage site.

But London’s club scene faced new threats. Rising rents, licensing laws, and noise complaints from new luxury apartments in Shoreditch and Peckham forced many venues to close. The Cross in Camden shut down in 2007 after 20 years. The Wag in Soho, a staple for queer nightlife since 1978, closed in 2013. The city was becoming less tolerant of noise, less willing to protect spaces for the young, the strange, and the loud.

Still, innovation survived. In 2012, Printworks opened in a former printing factory in Rotherhithe. It had 10,000 square feet of industrial space, no ceilings, and a sound system that could shake concrete. It became the new spiritual home for techno and house. Meanwhile, The Jazz Cafe in Camden kept live jazz alive, and The Windmill in Brixton became the birthplace of the UK’s punk and indie revival.

2020s: Resilience, Diversity, and the New London Sound

After the pandemic, London’s club scene didn’t just return-it reinvented itself. The rise of Afrobeats, UK drill, and garage 2.0 changed the sound. Clubs like Love Saves the Day in Kings Cross now host open-air raves with DJs from Lagos, Kingston, and Luton. Defected Records runs weekly house nights in Dalston that draw crowds from across Europe.

Queer spaces are thriving again. Stonewall Inn (a London tribute to the New York landmark) and Club Kali in Vauxhall are safer, louder, and more inclusive than ever. Black-owned venues like Black Girl Magic in Peckham and Yard in Brixton blend dancehall, soca, and house into something uniquely London.

Even the old guard is evolving. Fabric still books top-tier techno artists, but now it also hosts community workshops on sound engineering for teens from Tower Hamlets. Ministry of Sound hosts free Sunday sessions for local schools. The clubs aren’t just venues anymore-they’re cultural anchors.

Why London’s Dance Clubs Matter

London’s dance clubs have always been more than music. They’ve been places where people who didn’t fit elsewhere found belonging. Where immigrants brought their rhythms and made them British. Where queer youth danced when society told them to hide. Where a teenager from Croydon could hear a bassline that changed their life.

Today, as property developers eye every empty warehouse and councils tighten noise limits, the fight to protect these spaces is real. But Londoners know: if you want to understand the soul of this city, you don’t go to the Tower or Buckingham Palace. You go to a basement in Hackney at 3 a.m., where the lights are low, the crowd is diverse, and the music is still changing the world.

Wat zijn de beste danceclubs in Londen vandaag?

Voor techno en house is Fabric in Farringdon de meest gerespecteerde locatie. Ministry of Sound in Elephant & Castle blijft een topbestemming voor mainstream house en live acts. Printworks in Rotherhithe is de grootste ruimte voor immersive techno-avonturen. Voor afrobeats, drill en urban muziek zijn Yard in Brixton en Black Girl Magic in Peckham onmisbaar. En voor queer- en alternatieve cultuur: Club Kali in Vauxhall en The Windmill in Brixton.

Waarom sluiten zoveel clubs in Londen?

De belangrijkste redenen zijn hoge huurprijzen, nieuw gebouwde luxe appartementen naast oude clubs, en strenge geluidswetten. Veel clubs liggen in wijken die worden gentrificeerd, zoals Shoreditch en Peckham. Bovendien zijn de vergunningen voor nachtclubactiviteiten duur en moeilijk te krijgen. De overheid heeft lange tijd geen financiële steun geboden voor culturele ruimtes, waardoor clubs moeten concurreren met cafés en restaurants die minder lawaai maken.

Is het veilig om alleen naar een club te gaan in Londen?

Ja, in de meeste gevestigde clubs is het veilig, vooral als je naar bekende locaties als Fabric, Ministry of Sound of Printworks gaat. Ze hebben professioneel beveiliging, CCTV en duidelijke nooduitgangen. Voor kleinere, alternatieve clubs is het verstandig om eerst online reviews te lezen of met een vriend te gaan. Vermijd onbekende plekken in afgelegen gebieden, vooral na middernacht. Gebruik altijd Uber of de Night Tube (lijn N29, N38, N550) om veilig terug te keren.

Welke muziekstijlen zijn het meest populair in Londense clubs?

De meest populaire stijlen zijn nu afrobeats, UK garage 2.0, drill, en deep house. Techno blijft sterk in Fabric en Printworks, terwijl bass music en jungle terugkeren in clubs als The Windmill en The Shacklewell Arms. Afrobeat is nu de dominante stijl in Brixton en Peckham, met DJs als Burna Boy en Tems die regelmatig live optreden. Garage, met zijn typische 2-step beat, is de soundtrack van de jonge generatie in Hackney en New Cross.

Hoe kan ik een clubbeleid vinden dat niet te duur is?

Veel clubs bieden gratis of goedkope entrees op weekdagen, vooral op zondag of maandag. Check de Instagram- en Twitter-accounts van je favoriete clubs-ze geven vaak kortingen voor eerste bezoekers of studenten. Ook zijn er gratis events bij kunstgalerijen zoals Tate Modern of de Southbank Centre, die vaak muziek en dans integreren. Abonneer je op newsletters van Resident Advisor of London Nightlife, waar je dagelijks updates krijgt over goedkope en unieke avonden.